Why the Midwest's 'Cool' Summer is Misleading: The Hidden Heat and the Global Climate Crisis

Unfortunately, the limited warming hurts perception.

Iowa saw its 70th warmest summer on record. In the meteorological world, summer is over. Yes, this week doesn’t feel like that, but there is a reason *we* (meteorologists) don’t use astronomical seasons. Meteorological summer is based on the annual temperature cycle which runs from June 1 to August 31, making it easier for climatologists to analyze and compare data year to year. In contrast, astronomical summer is determined by the Earth's position relative to the Sun, starting around June 21 with the summer solstice and ending around September 21 with the autumnal equinox. The main difference is that meteorological summer follows the calendar for consistency, while astronomical summer is tied to Earth's orbit.

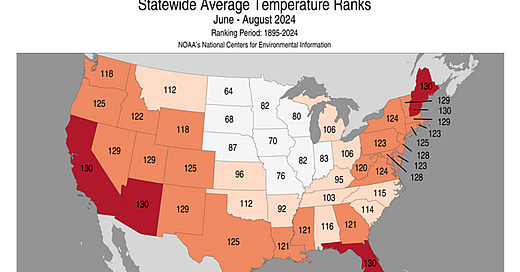

If you look at it city by city, Des Moines experienced its 40th warmest summer on record, and Waterloo recorded its 21st warmest. When talking about the impacts of climate change, it is important to understand that it involves more than what is happening in your backyard. For example, the was the 4th hottest summer on record in the United States, but it was the hottest on record globally. While the Midwest saw a seasonably warm summer, Arizona, California, Florida, Maine and New Hampshire all recorded their hottest summer on record.

Why Is the Midwest Cooler

The paper titled "Why Has the Summertime Central U.S. Warming Hole Not Disappeared?" investigates the persistent phenomenon known as the "warming hole" in the central United States—a region where summer temperatures have not increased as rapidly as global averages despite ongoing climate change. The researchers aim to understand why this anomaly continues to exist when models predict it should have diminished.

The study analyzes historical climate data and employs climate models to identify the factors contributing to this regional cooling effect. The authors find that increased soil moisture due to enhanced precipitation leads to higher evapotranspiration rates. This process cools the surface and increases cloud cover, which reflects sunlight and further reduces surface temperatures. Additionally, changes in atmospheric circulation patterns, such as shifts in the jet stream and storm tracks, have reinforced these cooling trends by bringing cooler air into the region.

The paper concludes that the interplay between land surface processes and atmospheric dynamics is crucial in maintaining the warming hole. These localized factors counteract the broader warming trends caused by greenhouse gas emissions. The authors emphasize the importance of incorporating regional climate dynamics into global climate models to improve the accuracy of future climate projections. Understanding why the warming hole persists helps scientists better predict regional climate variations in the context of global warming.

Another factor at play? Corn sweat. While it might not have felt like a seasonable summer, it was incredibly humid. Heat indices climbed into the triple digits several times, but the air temperature never actually made it there this summer in Des Moines. The heat index considers the air temperature and humidity. (Think of the heat index as the first cousin of the wind chill. Essentially it is what the temperature feels like.) Corn sweat leads to humidity and humid air is a lot more difficult to warm up than dry air.

Unfortunately, for those who lack a worldly view, they don’t understand the gravity of climate change. According to the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, the greatest percentage of the population who don’t feel that humans are causing climate change are those in the Midwest. Although it’s tough to prove, I am certain it fuels the doubt.

Bigger Picture of Summer 2024

While extreme heat events are becoming more frequent and severe, 2024’s record heat was not confined to just one region. Parts of the Southwest, including Phoenix, experienced weeks of temperatures above 110°F. Heat waves disrupted lives, increased energy demands, and exposed the vulnerability of infrastructure, particularly in regions unaccustomed to extreme temperatures. Arizona and Nevada saw record-breaking days, while coastal states like Florida faced a perfect storm of heat and humidity, making conditions unbearable for residents and tourists alike.

Beyond the sheer discomfort of this summer, its aftermath paints a grim picture. Agricultural sectors across the country suffered from the prolonged heat, exacerbating issues already at play with the changing of growing seasons. The energy grid was pushed to its limits as air conditioning became a lifeline for millions. Public health crises intensified as emergency rooms saw a spike in heat-related illnesses and deaths.

These conditions, however, are not isolated incidents. This summer is part of a broader pattern of increasingly hot seasons, driven by the growing concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. It raises critical questions about how communities can adapt to these new extremes, from improved building designs to more efficient energy systems.

While adaptation is crucial, so is addressing the root cause of the problem. The U.S. and the global community must accelerate efforts to reduce carbon emissions and transition to renewable energy sources. The 2024 summer is a sobering reminder that the cost of inaction is measured not only in degrees but also in human lives and economic devastation.

As we look ahead to future summers, the need for comprehensive climate action has never been more urgent. The lessons from 2024 should serve as a wake-up call for governments, businesses, and individuals to step up and mitigate the future impacts of extreme weather.

Another Billion-Dollar Disaster, Which Impacted Southern Iowa

The severe weather event which became the 20th billion-dollar disaster in 2024 occurred in mid-June and impacted the central and eastern United States. This event was characterized by a series of strong thunderstorms that produced destructive winds, hail, and tornadoes. It caused widespread damage across multiple states, affecting homes, businesses, and infrastructure.

In particular, these storms brought dangerous wind speeds, damaging crops and property, and leaving thousands without power. The central U.S. was hit hardest, with severe thunderstorms stretching across regions like the Midwest and parts of the Southern U.S. This event further illustrates the increasing frequency of billion-dollar disasters linked to climate change, as these weather patterns become more extreme and persistent.

I am happy to be part of the Iowa Writer’s Collaborative!

Thanks for this important analysis.